Both prematurity and low birth weight can put an infant at significant risk of death. In 2013, an estimated 36% of infant deaths were due to preterm-related causes, according to a paper published in National Vital Statistics Reports in 2015.

Black infants are about twice as likely to be born at low birth weight and 1.5 times as likely to be born prematurely than white infants.

Yet the new study finds that Medicaid expansion was linked with closing that gap.

Between 2011 and 2016, this expansion was associated with significant improvements in disparities among black and white infants, according to the study, published Tuesday in the medical journal JAMA. Enrollments for insurance under the ACA began in 2014.

"It's one more piece of the puzzle that points to the gains in health from Medicaid expansion, especially to certain populations," said J. Mick Tilford, professor and chair of health policy and management at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, who was senior author of the study.

"We believe that these findings should be considered in policymakers' calculus of whether to expand Medicaid or not," he said.

Anyone can qualify for Medicaid based on income, household size, disability, family status and other factors, but the ACA allows states to expand Medicaid eligibility so that residents can qualify based solely on whether their household income level is a certain percentage below the federal poverty line.

"We hypothesized that health insurance would make mothers healthier," Tilford said.

"If mothers had more health insurance and better health, then it would affect the health of the baby. That's what we think is driving the results in this study, is the healthier mother," he said. "There's a lot of factors that affect low birth weight, but nothing comes close to these differences in outcomes by race."

A 'between 5% and 15%' effect

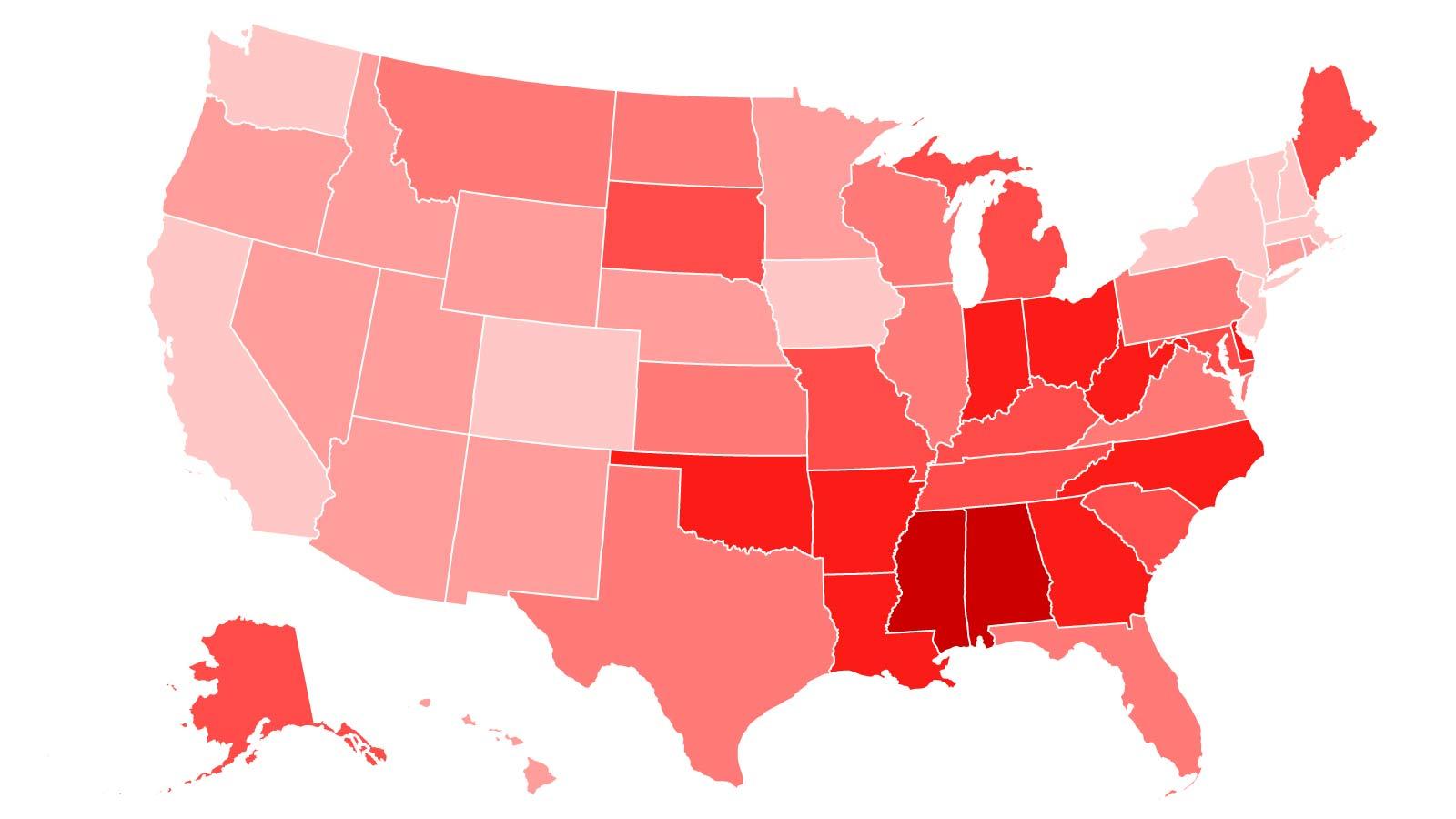

The researchers analyzed birth certificate data on more than 15 million births to women 19 and older across the District of Columbia, 18 states that expanded Medicaid and 17 states that did not. The data, which dated from 2011 to 2016, came from the National Center for Health Statistics' Vital Statistics System.

Among black, white and Hispanic infants, the researchers took a close look at the health outcomes of low birth weight, preterm birth, very low birth weight and very preterm birth. They then compared outcomes in states that expanded Medicaid with those in states that did not.

Overall, the data showed no differences in those birth outcomes between expansion and nonexpansion states. However, differences in rates of outcomes for black infants compared with white infants in Medicaid expansion states shrank, with improvements seen in black infants across all four outcomes.

"The effect size for black infants in expansion states was between 5% and 15%," Tilford said.

No changes in relative disparities were seen for Hispanic infants, the researchers found, but for the black infants, "these reductions potentially have large implications across the life course of black infants," said Clare Brown, an instructor of public health at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, who was first author of the study.

The study had some limitations, including that because it relied on the birth data files, it was vulnerable to any limitations seen in that dataset.

"There are a lot of variables that we wish we could have controlled for. A great one would have been to be able to look specifically at women who were low-income," Brown said.

"The birth certificate data doesn't have any indicator of whether or not a woman, for example, had an income below 138% of the federal poverty level, which would make her eligible for Medicaid under Medicaid expansion," she said.

A 'major public health concern'

This isn't the only study to find a significant association between Medicaid expansion and certain health outcomes.

Research presented at the American Heart Association's Scientific Sessions this month found that between 2010 and 2016, counties in states where Medicaid expanded had 4 fewer deaths per 100,000 residents each year from cardiovascular causes compared with counties in nonexpansion states.

Dr. Heather Burris, attending neonatologist at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania's Perelman School of Medicine, called the new study "elegantly designed."

"The investigators found that while expansion was not associated with overall differences in birth outcomes, there was a reduction in black-white disparities, which has historically been very difficult to do," said Burris, who was not involved in the study.

She added that the disparities highlighted in the study are still "of major public health concern."

For instance, the receipt of prenatal care in the first trimester is still low among black women in both expansion states, at 67%, and nonexpansion states, at 64%, compared with white women at 81% and 78%, respectively.

"These ongoing disparities highlight that more than just health care access is necessary to resolve racial disparities in birth outcomes," she said.

There are many pathways by which Medicaid expansion might influence pregnancy outcomes, including increases in women's access to prenatal care, said Michael Kramer, an associate professor of epidemiology at Emory University's Rollins School of Public Health in Atlanta, who was not involved in the study.

Also, "one mechanism by which Medicaid expansion could help is by supporting more consistent and comprehensive family planning," Kramer said.

"Finally, we believe that important causes of all outcomes -- and also causes of racial disparities in outcomes -- arise from differences in women's health before they ever got pregnant," he said.

"The benefits of consistent access to health insurance and health care may accrue across years to result in improvement in women's health generally. This would translate to improved pregnancy outcomes but might not be apparent with only one or two years of expansion status," he said. "In other words, it is critical we continue to evaluate the longer term impacts Medicaid expansions."

No comments:

Post a Comment